by Jo Henwood

This year, the Sydney Fairy Tale Ring has begun meeting to share what we call Magic Movies – fairy tale films from around the world – as another creative form that interprets the many strands of fairy tales; and there are many films to choose from.

Why? What is it about fairy tales that attracts film-makers to create their own interpretations?

The earliest motivation, back in 1890s France, was simply to show what film could do. Georges Melies was the best-known of these innovators, using stop animation to create magical appearances, puppets, costumes and coloured slides to tie them to a narrative already popular through pantomimes. Those first audiences must have gasped in wonder.

In a way, Melies was following on from earlier forms of fairy tales as spectacles, known as feerie. Even before 17th century French Salons nurtured the performance of original fairy tales, the old oral stories were displayed in a sort of living statue form as outdoor entertainments for the aristocracy. After the 1789 revolution, a new proletariat audience watched their own versions of feerie, while over in England, James Plance presented what he called fairy tale Extravaganzas.

Only a generation later, German artist Lotte Reiniger created the world’s first animated fairy tale film, Prince Achmed (1926), to use her stunning paper-cut shadow puppetry in stop animation with full colour to create a stunning work of art.

But of course, Prince Achmed‘s fame has been well and truly eclipsed by Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1937, the beginning of world-wide dominance over the genre, so that other visions had little chance of being seen. Disney only paused in their fairy tale film production when the exquisitely animated and scored Sleeping Beauty failed commercially in 1959, (only to be resumed with 1989’s The Little Mermaid), just at the time that Japanese animated films took off with their version of the Chinese story, The White Serpent (1958).

To add to the struggles of making any sort of film in post-war France, director Jean Cocteau created La Belle et la Bete (1946), with magnificent costumes made almost from rags, and using techniques like making candles light up in sequence by blowing them out then running the film backwards. The Italian-Spanish mini-series Fantaghiro (1991) from Italo Calvino’s, Fantaghiro the Beautiful, had a much easier time of it with special effects.

BBC One animated the illustrations of Quentin Blake to their re-fracturing of Roald Dahl’s fractured fairy tales in six comic poems, Revolting Rhymes (2016), not with drawing but with computer animation, slipstreaming on what Tangled achieved in 2010. And some films live on mostly because of the costumes, like the French film Donkeyskin (1971) starring Catherine Deneuve.

Other film-makers use the template of fairy tale narratives to communicate their own messages for their own time. The most popular fairy tales, retold in film after film in Europe, America, and to a much lesser extent, Asia, are Cinderella, Little Red Riding Hood, Hansel and Gretel, Snow White, Bluebeard – as you would expect – have been used in many different genres.

In the 1930s and 1940s Hollywood, there were many shorts that parodied fairy tales for slapstick humour and occasionally for satire, e.g. Max Fleischer’s Betty Boop as Cinderella, Looney Tunes’ Little Red Riding Habit, Tex Avery’s Peachy Cobbler.

Cinderella was used to transform child star Deanna Durbin into romantic roles. Powell and Pressburger’s story told of the price of being an artist in the spellbinding Red Shoes (1948), and Jannik Hastrup extended that to look at what happens to the artist when what they have created lives beyond them in Hans Christian Andersen and the Long Shadow (1998) though it has not been translated into English, so most of us will never know how good it might be.

Political comments were made in communist era Czechoslovakia in Karel Zeman’s King Lavra (1948), a retelling of King Thrushbeard, the flood of Soviet fairy tales starting with Ivanov-Vano’s The Humpback Horse (1947), and in the French film, Paul Grimault’s The King and the Mockingbird (1979), a version of Andersen’s The Shepherdess and the Chimney Sweep that proclaims the values of freedom.

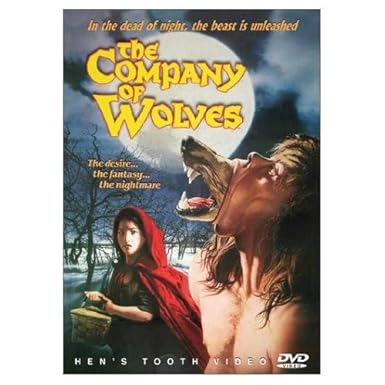

The world of fairy tale interpretation was transformed by Angela Carter’s book of retellings, The Bloody Chamber, which was followed by Neil Jordan’s film version, In the Company of Wolves. Horror fairy tale retellings came in the aftermath. That is probably the favourite use of fairy tales in Asia, with films such as A Tale of Two Sisters (2003) from Korea, as well as Little Otik (2000) from the Czech variant of Hans, My Hedgehog, and the American Hard Candy (2005), based on Little Red Riding Hood.

Women with power could be seen in such 21st century films as Blancanieves, a fractured version of Snow White (Spain 2012), Tale of Tales (Italy 2015), a reworking of Basile’s collection, and Green Snake (China 2021), as well as all the Add-A-Sword films like Snow White and the Huntsman (2012).

Some film-makers chose to avoid retellings in favour of creating new fairy tales specifically for film, such as Michael Ocelot’s Azur and Asmar (2006) and his Kirikou films (1998, 2005), Pan’s Labyrinth (Spain 2006) and many others.

Fairy tale films are also created to reach a particular audience, whether that be cultural – as in the massive output from Russia, Hungary, and the Czech Republic, such as the Christmas favourite Three Nuts for Cinderella (1973), and the 2010 Chinese film of the oldest Cinderella, Yeh Shen.

For the child and family market dominated by Disney, Don Bluth, also American, created some competition in the 1980s, with films such as Swan Princess (1994) made because they believed Disney was purely motivated by avarice with no concern for art (surely not!). Disney responded with Little Mermaid (1989) to begin its renaissance. In spite of all Bluth’s efforts, it was Pixar’s Shrek (2001) that really shook up the notion of what fairy tale-themed films could be, while Studio Ghibli’s success with Princess Kaguya (2013) had a lot to do with not being in competition for the same audience.

Where does Australia lie in all of this? Very much at the rear, I’m afraid.

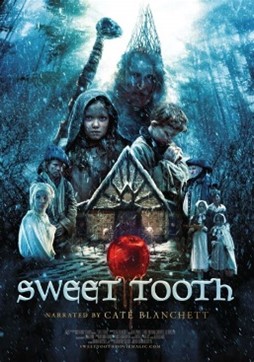

Australian rainforests and what was described as ‘Aboriginal mythology’ were used as the backdrop for the original environmental message movie, Fern Gully (1992), with American actors and occasional faux Aussie accents. This century, there has been the unsavoury and dreary Jane Campion fractured version of Sleeping Beauty (2011), and the Cate Blanchett-narrated short film of Sweet Tooth (2019), a retelling of Hansel and Gretel set in Europe but with Australian actors.

There are so many possibilities for what could be created next.

Further reading: Zipes, Jack. The Enchanted Screen: The Unknown History of Fairy-Tale Films. Routledge, 2011.