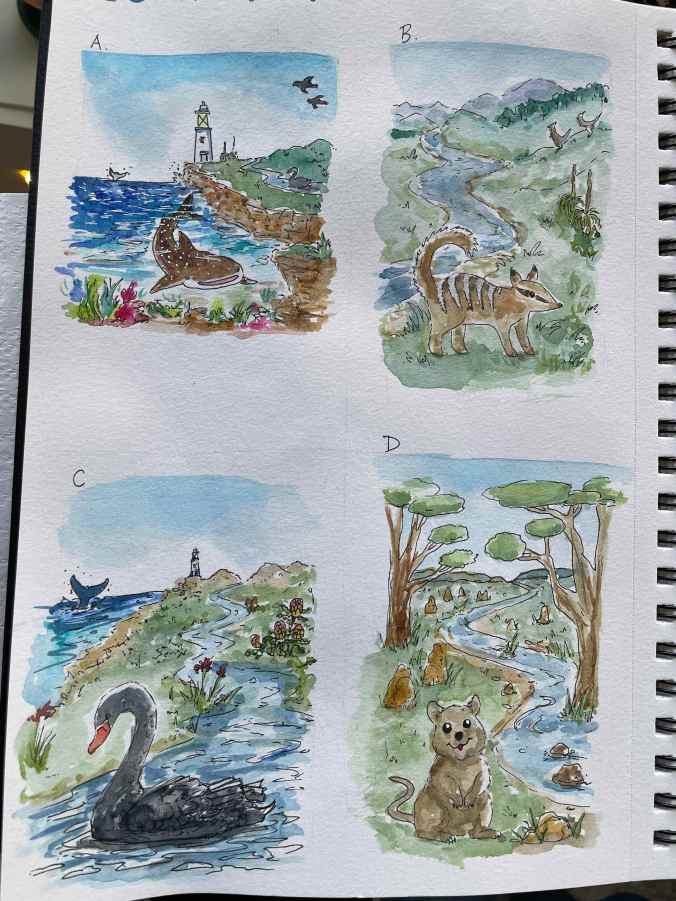

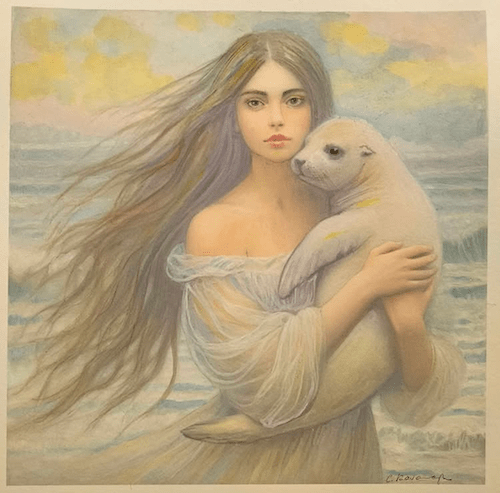

Come August 15-16, we’ll be Melbourne-bound for our 2026 conference, Witches in Fairy Tales: Wise Women or Evil Enchanters, as gloriously illustrated by Cassandra Kavanagh. Learn more in part 1 of our interview with this magical creator.

What drew you to fairy tales as a child?

I could read at age four, and the first books I was given were fairy tales. I believed every word. As I was a rather odd child with endless annoying questions, I was constantly sent down to the back of the garden to find the fey folk. I always took a fairy tale book with me to read out loud to the fairies. But the big golden event that was an everlasting shining moment in my life was being taken to an antique bookshop for my fifth birthday. The wonderful, enchanting old woman who owned this magical place showed me her favourite book. It was vast, heavy and old, stitched with gold thread, and the jewel-bright illustrations were protected by sheets of transparent rice paper, edged with gold. Fey-folk, fairies and old gods and goddesses wove their way through the pages like an enchantment. They felt familiar, as if in some other time and in some other life I had sat around a fire and heard these stories that seemed to still sing in my blood and had once warmed me over winter. The book beckoned like a doorway into another realm I belonged to.

What draws you to them now?

Fairy tales tell us who we are, how to be, and, more important still, how not to be. Fairy tales hold powerful reminders that resilience, true love, transformation and redemption are possible. They teach us that actions have consequences, often unforeseen. These time-upon-time tales that are passed down over hundreds, even thousands of years, hold ancient wisdom and warnings. They connect us to people in the past who had important things to tell us that still resonate now.

Do you have a favourite fairy tale?

Such a hard question. I love so many! However, I have always been drawn to Beauty and the Beast, and the numerous variations of the animal bridegroom in fairy tales. In particular, I adore the European stories featuring grey, white or silver wolves.

Do you have a least favourite?

I received Bluebeard for my seventh birthday and remain traumatised to this day. The story shook me to my bones! The illustrations were oddly beautiful, in stark contrast to their subject matter. The artwork depicting six murdered brides in long flowing gowns hung on meat hooks, while their blood pooled in swirls of pink and crimson beneath their pretty shoes, was truly horrifying. And as an incredibly curious child, I knew I would have disobeyed Bluebeard and opened the forbidden door with the mysterious key!

Tell us about the Illawarra Fairy Tale Ring*

Our Fairy Tale Ring meets on the last Thursday of every month. If I had more powerful magic, I would make it every week! It’s my favourite day of the month. Our amazing Ring Maidens, Pat Simmons and Helen McCosker, make it a truly magical experience. We pick a theme and an artist to study every month, and I am excited and enthralled every time. We all get along, and we are all a bit naughty in the nicest sense of the word! I have finally at long last found my tribe, and the experience is magical and enchanting. The Ring is like a magical box, with all the women-folk as the treasures.

Has being part of the Fairy Tale Ring inspired your art?

The members have been super supportive of my art, but the best is yet to come! I’m so inspired. Expect to see a lot more fairy-tale-inspired art from me! I am definitely going to paint more witches, and I have many that include fairy tale motifs and animals.

How long have you been painting?

I’ve been painting since the age of two, really as soon as I could hold a pencil or a paintbrush!

What inspired your early work?

I was inspired in equal measure by nature and by fairy tales, folklore, myths and legends. My birthday and Christmas presents were always books about these things. I was seriously bullied at school, so I would take my books and my sketch book and paints into the woods behind our house and sit by the stream. There I felt free to be me.

How has your art changed over time?

What has changed is my greater passion to put beauty and light back into a world that seems challenged by dark times. I have a new motivation to spread ancient and time-worn tales to a wider audience through my art – and I have become more passionate about reflecting paganism in my art, because the belief system honours the earth and her seasons while revering the natural environment and everything upon it. The smallest stone is as sacred as the forest.

What are you most looking forward to about this year’s Australian Fairy Tale Conference?

I’m most looking forward to the magic! Gathering with a community that shares and understands your passion is always so exciting, inspiring, heart-warming, soul-stirring and nurturing. The kinship with kindred spirits is a true blessing! I’m looking forward to indulging in my passion for all things fairy tale and witchy! I am also thrilled to extend my interest and learn from others, and of course, share my art.

Until then, Cassandra’s gorgeous artwork can be viewed at Instagram.com/cassandrakavanagh

* The AFTS has many Rings around Australia, including Adelaide, Brisbane, Perth, Sydney and Victoria, plus ‘Magic Mirror’ (our online Ring) that all members can attend. More details here, or E: austfairytales<at>gmail.com.